For this exercise, I was asked to choose a minimum of 6 artists and research their sketchbooks, developing both visual and written research and using it as a starting point to create my own sketchbook work. I was asked to think about the artist’s work and how it resonates with me, responding visually to that rather than replicating what I saw. I was also encouraged to consider how I could learn from how the artist uses their sketchbook, whether they leave mistakes in or not, how they use materials, and whether anything is hidden.

The exercise provided answers from OCA students and staff on which artists sketchbooks inspire them. Emma Powell, the author, had listed her favourites too. Initially, I quickly googled a few of these artists but wasn’t finding myself inspired, and I didn’t want to risk wasting hours choosing the ‘right’ artists to research. I instead searched ‘artists sketchbooks’ to see what would show up and came across the publishing house Unseen Sketchbooks. The company’s focus is on publishing the never before seen works of artists in limited run books. The content in them varies from sketchbook work to unfinished or personal projects, and these were a fantastic starting point for my research.

I looked through the publications from Unseen Sketchbooks and picked a handful of artists whose work I felt drawn to. On reflection, I thought it would be best to also choose some artists from the list Emma had included, as my choices so far were quite ‘samey’ and were chosen based on qualities I was already inspired by. I knew I could learn a lot from the more famous artists out there, and I wanted to challenge myself to see how I could learn from anyone. I ended up with ten artists to research, but aware that I was unlikely to research all of them in one go. They are:

- Louise Bourgeois

- David Shillinglaw

- Jesús Cisneros

- Ed Merlin Murray

- Jim Stoten

- Frida Khalo

- James Jean

- Mu Pan

- Eugène Delacroix

- David Hockney

I decided to work through these at random rather than in order and to go into depth exploring how the artist works. I have added links to each of the artists so that their research sections can quickly be accessed. If there is not a link, that means I have not yet researched that artist.

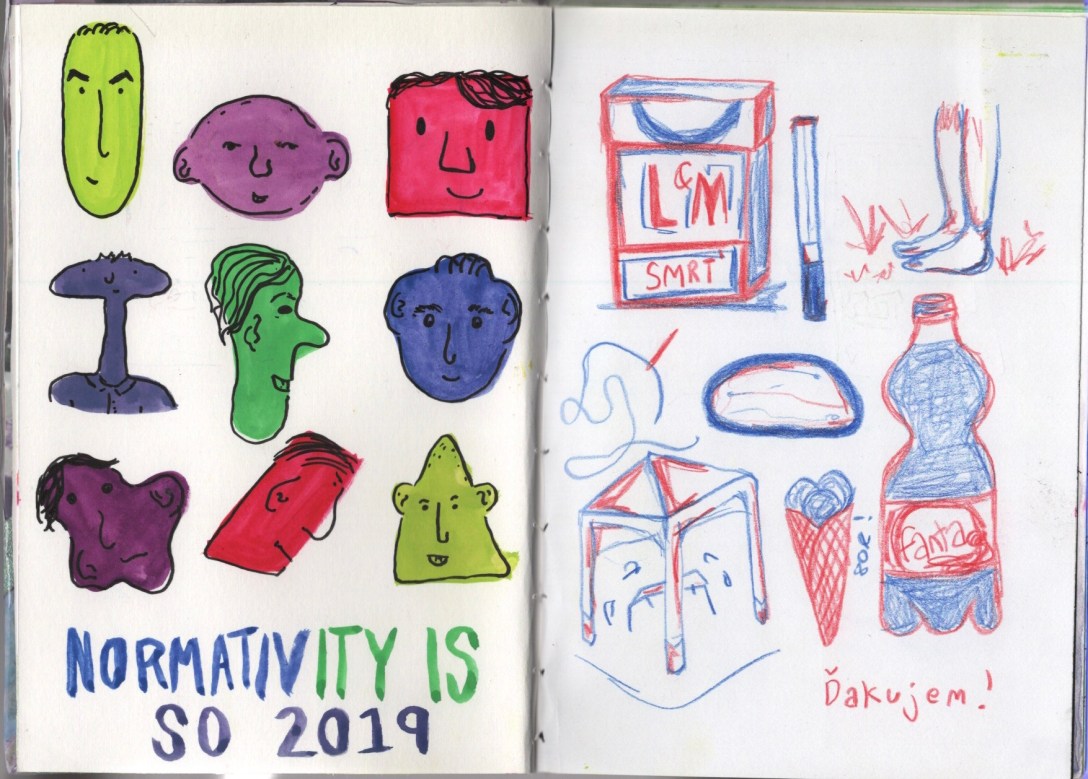

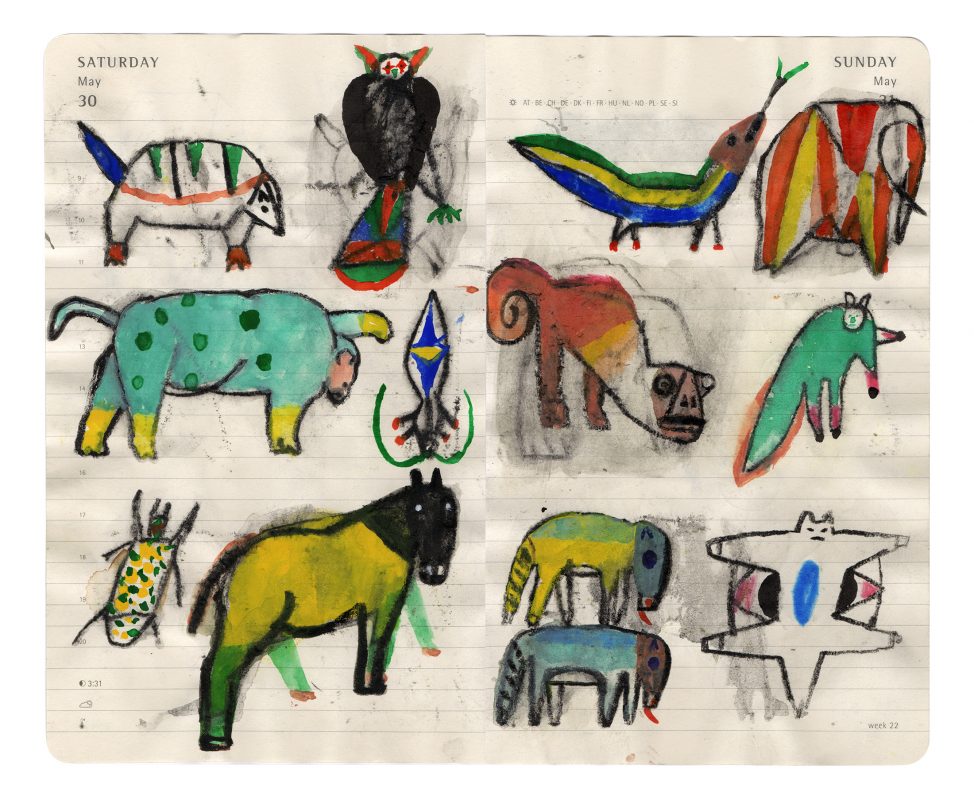

Jesús Cisneros

Six/Seis by Jesús Cisneros takes the viewer on a journey through Cisneros’s personal sketchbooks. The book takes it’s name from the six sections within – themes, series, memory, exploration, accidents, and fiction. Each section contains unedited work from the depths of Cisneros archive alongside interviews and text from the artist himself.

Whilst researching Cisneros, I referenced his biography on Unseen Sketchbooks, the listing page for Six/Seis on Unseen Sketchbooks, Jesús Cisneros’s Instagram account, and this YouTube video showing a flip through of the book itself. I do not have access to the book currently, but after having spent some time researching this artist, I am desperate to get my hands on it. I started by jotting down my thoughts on his work, the ways in which it inspired me, and what I could learn from his usage of sketchbooks.

I was particularly inspired by the names of the six sections of his book. I love this take on how we use sketchbooks and how almost everything we do in them could be put into one of those six categories. This prompted me to think about how I use my own sketchbook currently and whether there were any categories I could split my work into that were missing from his list. I probably wouldn’t use the word ‘series’ for any of my work, but I’m unsure what I could replace that with.

Cisneros’s sketchbook pages are messy, creative, playful, exploratory, and, best of all – fun. His consistent usage of bold neon colours paired with his seemingly intentional ‘mistakes’ is truly inspiring. Letting go, being free, and moving away from the perfectionism so commonly sought after in the artistic world, is a dream for many artists. Cisneros is achieving this perfectly. I described his work as ‘messy done with style’, and it’s a phrase I stand by and one I feel I could certainly learn a lot from.

Maybe it’s because the idea of ‘what kind of sketchbook should I use’ is already on my mind, but Cisneros’s usage of diaries as sketchbooks stood out to me especially. It adds to the playful carelessness of the work – almost as if he picked up the nearest book to him and just started working away. I mentioned in Exercise 1.0 that I’d like to work in second-hand books more, and seeing how Cisneros uses the diaries in this way furthered that desire.

There’s a great deal of experimentation within Cisneros’s pages. A lot of his work could be perceived as the first steps in a project – trial and error to discover how to perfectly achieve the look he is going for. This relates closely to how I’d like to use my own sketchbook: as an explorative space to take me from point A (an idea) to B (the finished project). Jotting down these notes and considering how I related to Cisneros’s sketchbook pages got my creative juices truly flowing, so I decided to move on to my visual responses.

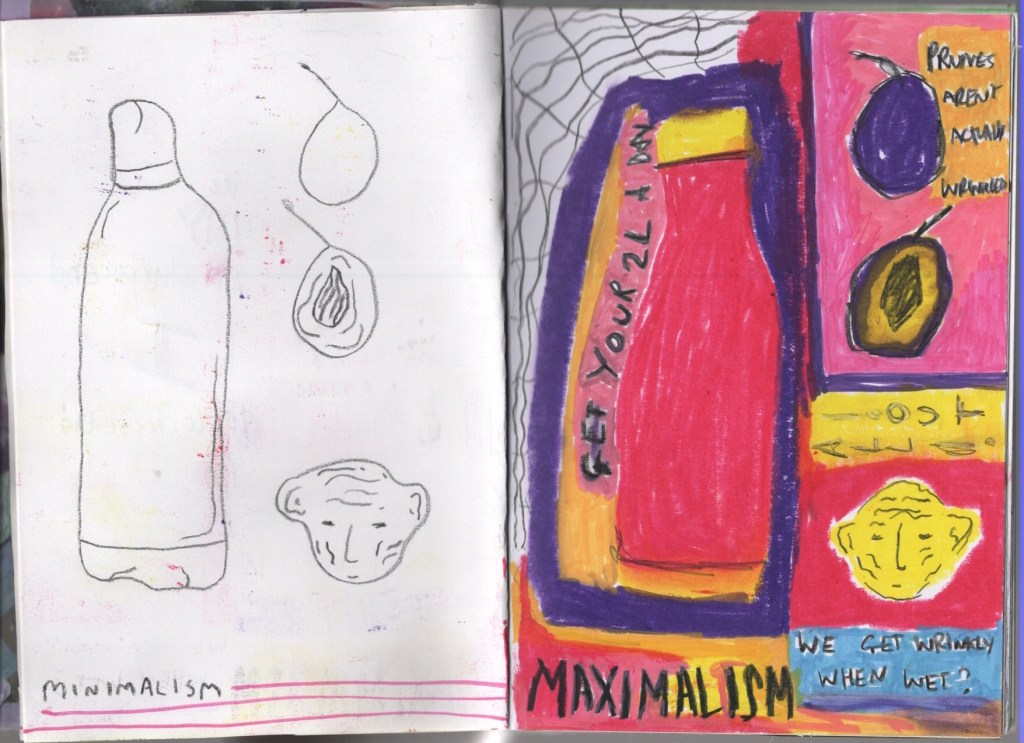

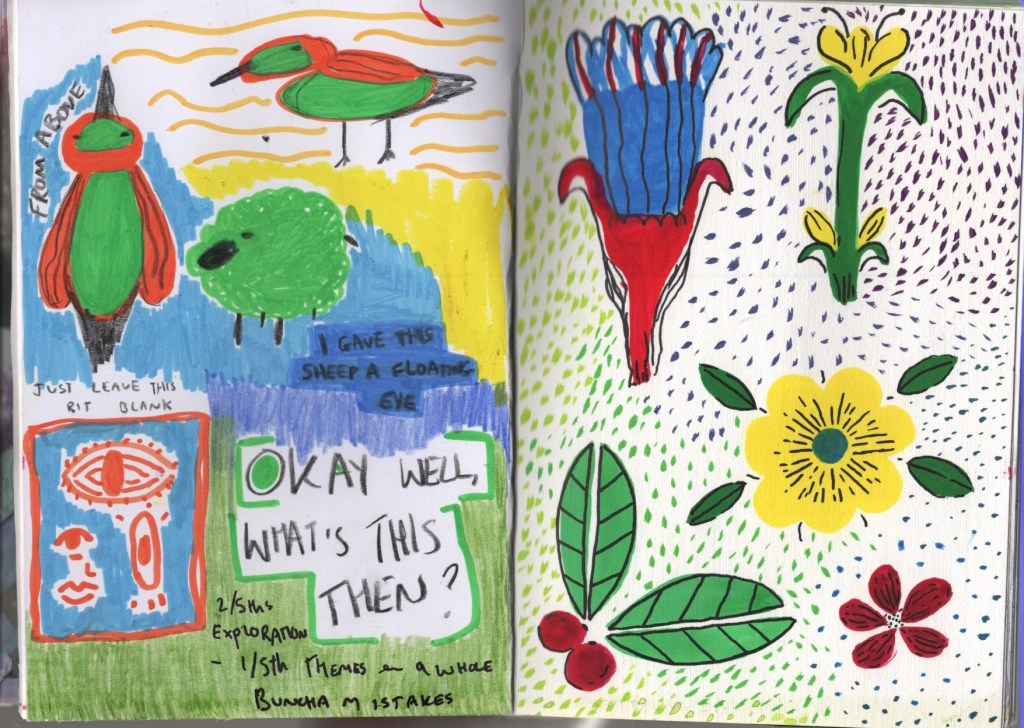

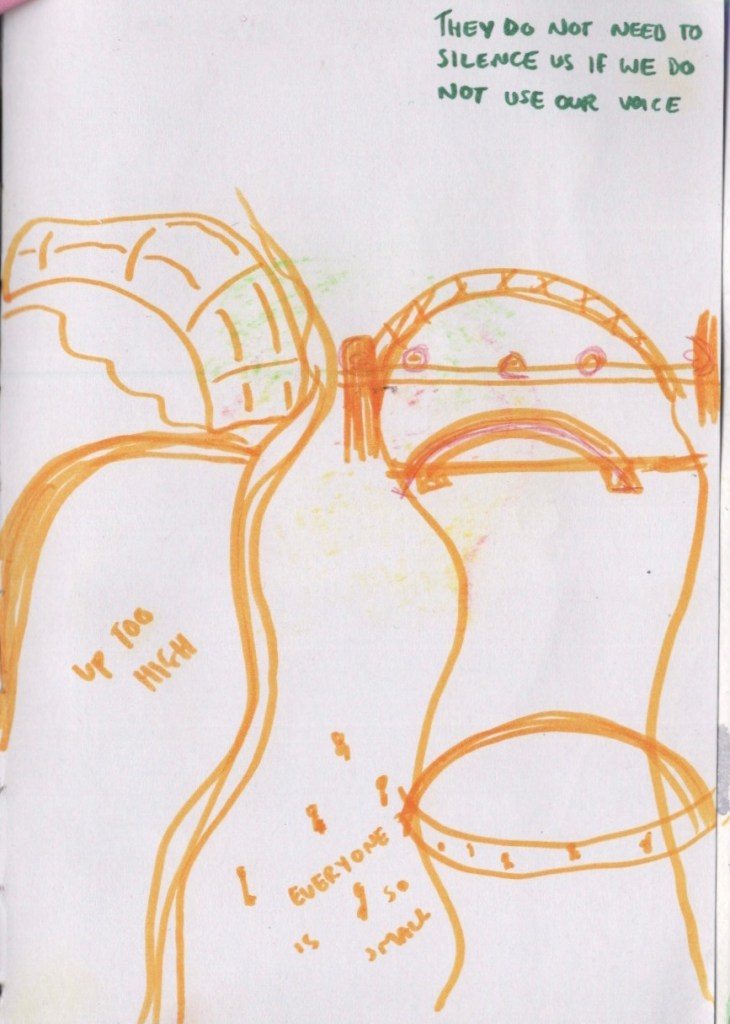

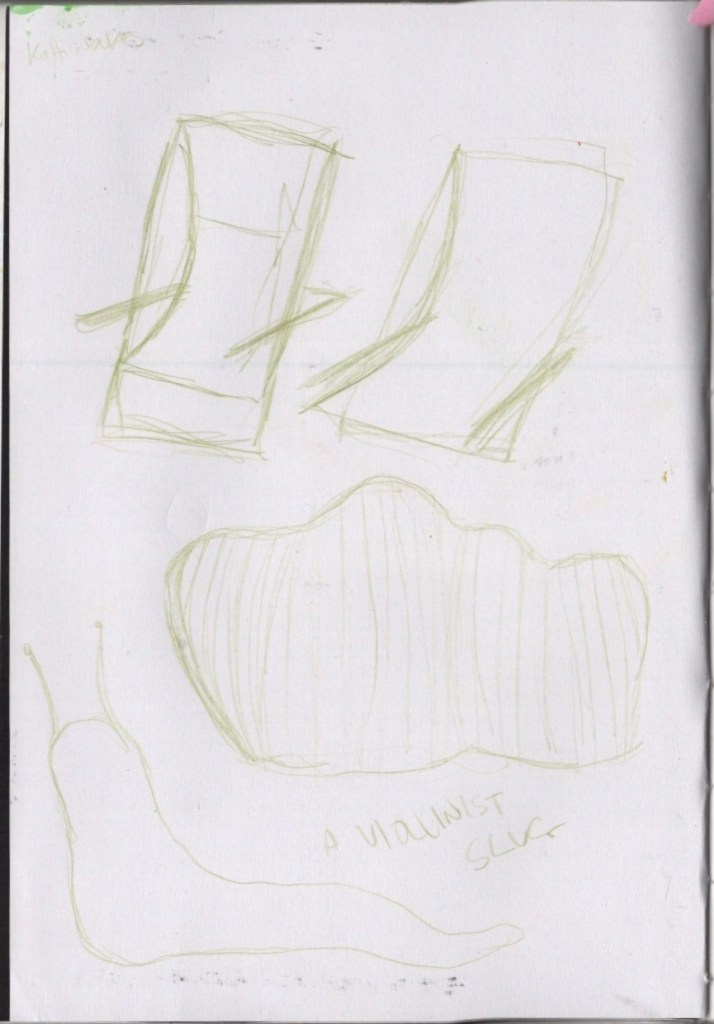

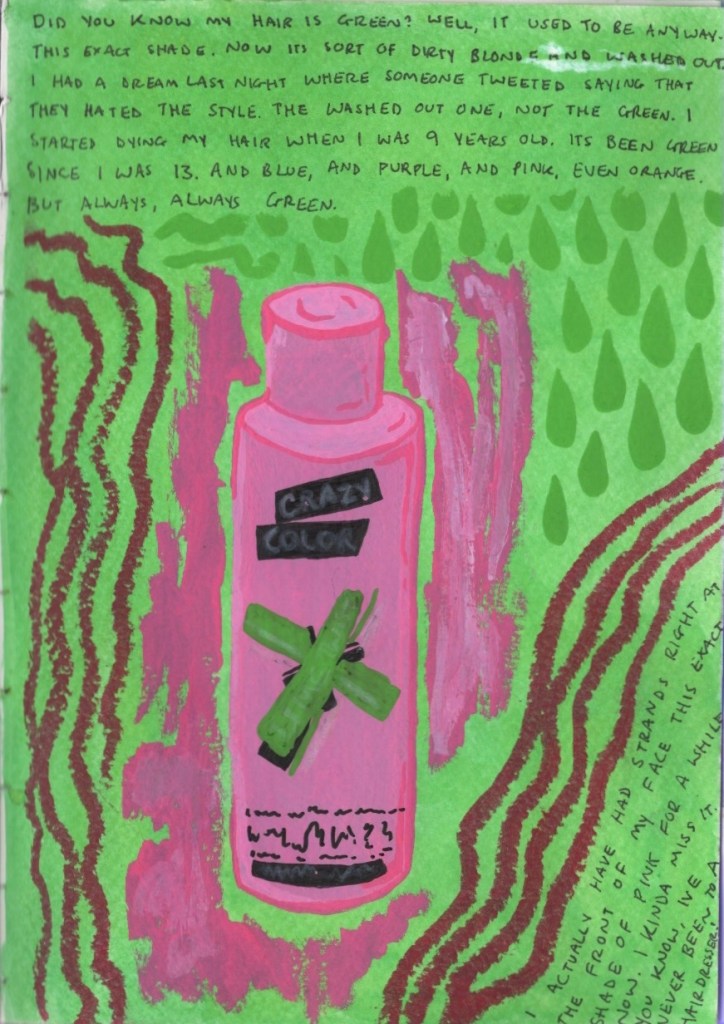

I loved the bold colours found in Cisneros’s sketchbooks, and I wanted to explore the playfulness he demonstrates in his work. I chose to use a combination of artists crayons, acrylic paint pens, and chinagraph pencils to start with, as these were bright and easy to get down on paper. I started with page 3 and drew what was right in front of me – my water bottle. I was thinking about the six sections of Cisneros’s book and how they related to my piece as I drew. ‘The everyday’ is a theme, one which prompted me to draw my water bottle to begin with. All of my work on the page was an exploration, and within the page, there were many accidents.

I sort of just let my mind wander whilst filling this page, seeing where it took me next. There was very little thought going into my actions, just a lot of ‘let’s see what happens when I do this!’. Together, my brain and hand took me on a journey around the page, from the water bottle to the prunes, then to the wrinkled old man. The busyness of the page and the chaos within led me to write ‘Maximalism’ at the bottom and inspired me to create the same thing on page 2 – this time from a minimalist perspective. Upon reflection, maybe ‘Journeys’ is a category that I could contain my work within.

Page 4 was an attempt at the same process I used on page 3, however I was less enthused this time. I feel the writing speaks for itself – I wasn’t enjoying the processs as much and couldn’t place it within the six categories easily. For this page I introduced some coloured pencils that I bought when I was visiting Slovakia on an Erasmus exchange in 2015. My mind was preoccupied with this, rather than with the work I was trying to complete. I realised ‘memory’ was one of the categories Cisneros had chosen for his book, so jumped to page 7 to draw my memory of that trip using the pencils.

Pages 5 and 6 are on acrylic paper, so I was eager to use paint for this. I was hoping to recreate, in my own way, the paintings Cisneros has done in his sketchbooks. I wouldn’t say I achieved that, but the goal of this exercise was not to copy his work, but to be inspired by it. I used gouache as I find it the most fluid and I once again let my mind wander to see where it took me. I really enjoyed this exercise and the process of letting go whilst working. I feel I have learned a great deal in completing these sketchbook pages, and researching Jesús Cisneros’s work has given me much food for thought.

David Hockney

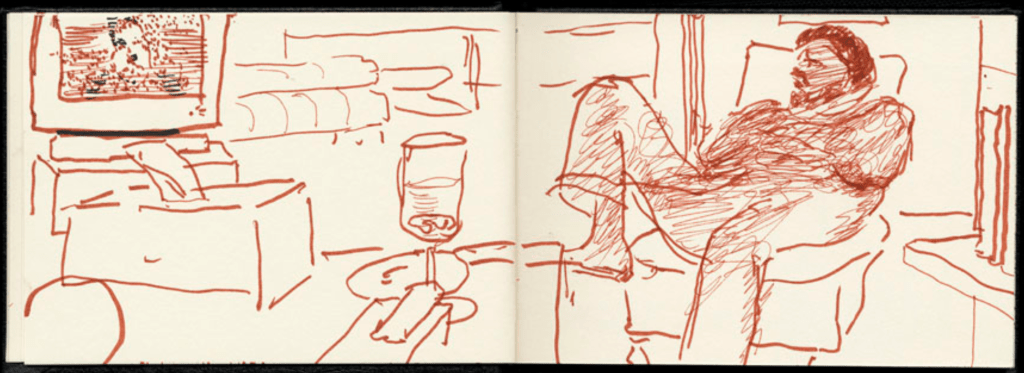

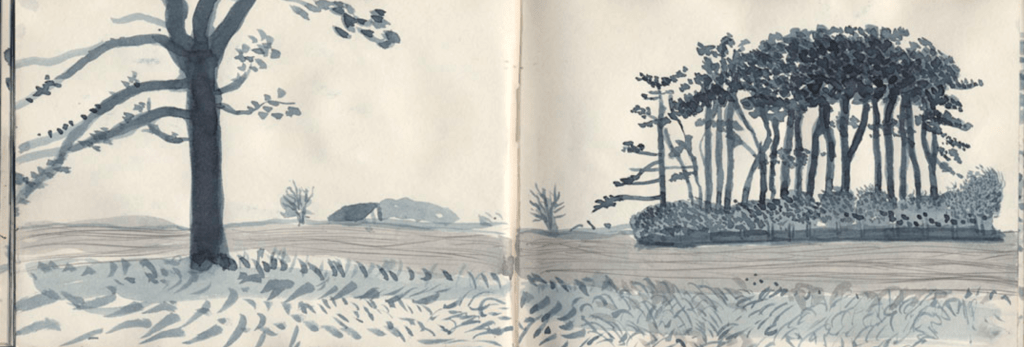

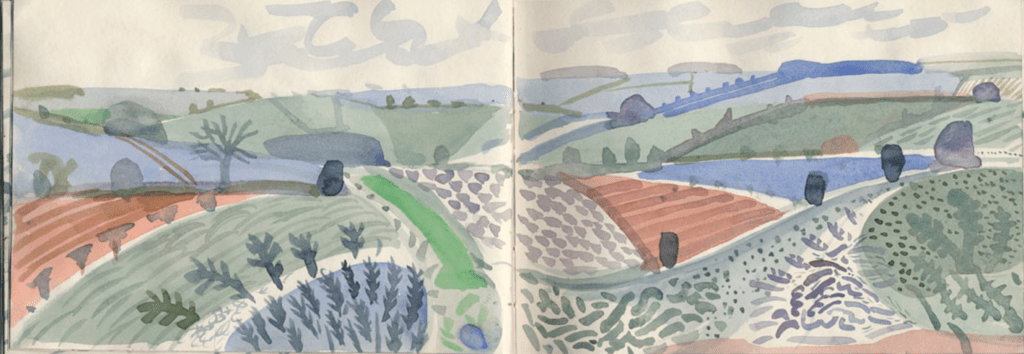

David Hockney is known for his contributions to the pop art movement. A quick google shows a clear, expressive style, with bold and rich colours used throughout his pieces. His sketchbooks, however, show an entirely different world. Their content is not so far removed from his paintings that they seem to be produced by another artist, but they are comparatively bland and lacking. You can tell that these sketchbooks are places for him to simply explore options, ideas, and the world around him.

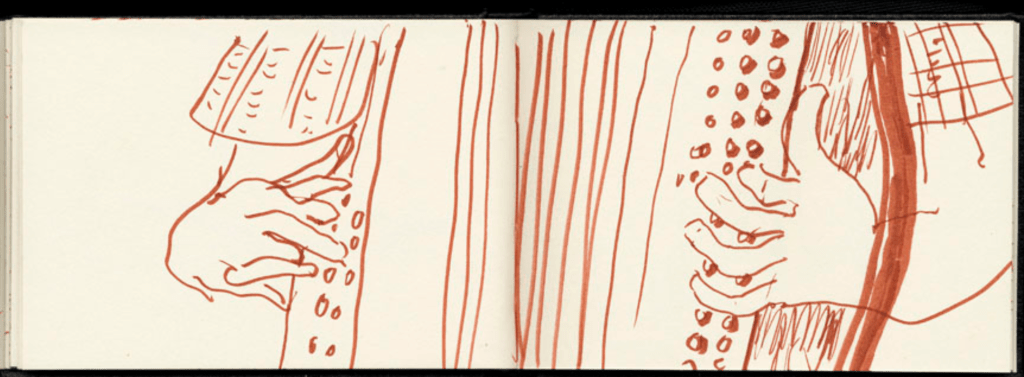

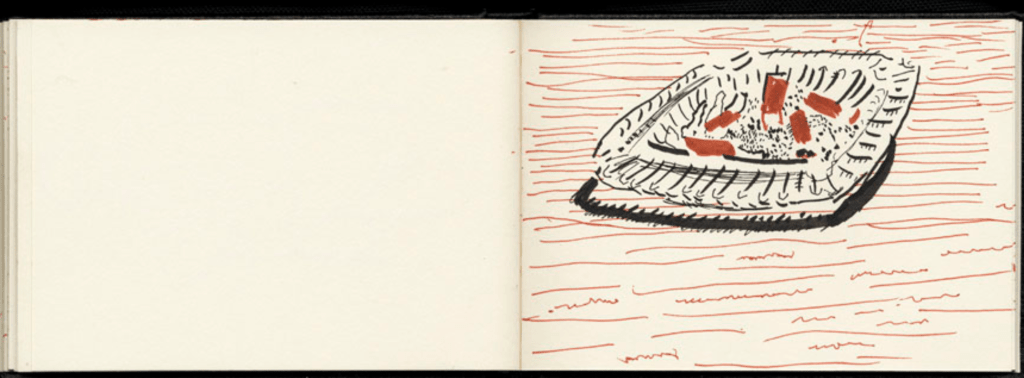

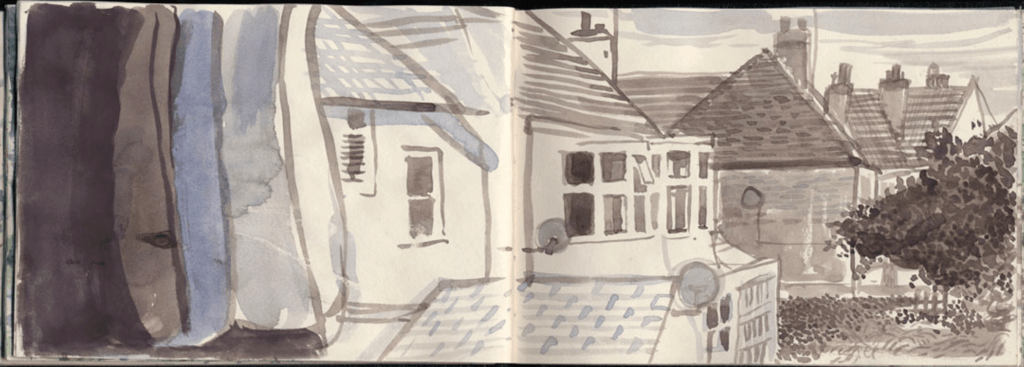

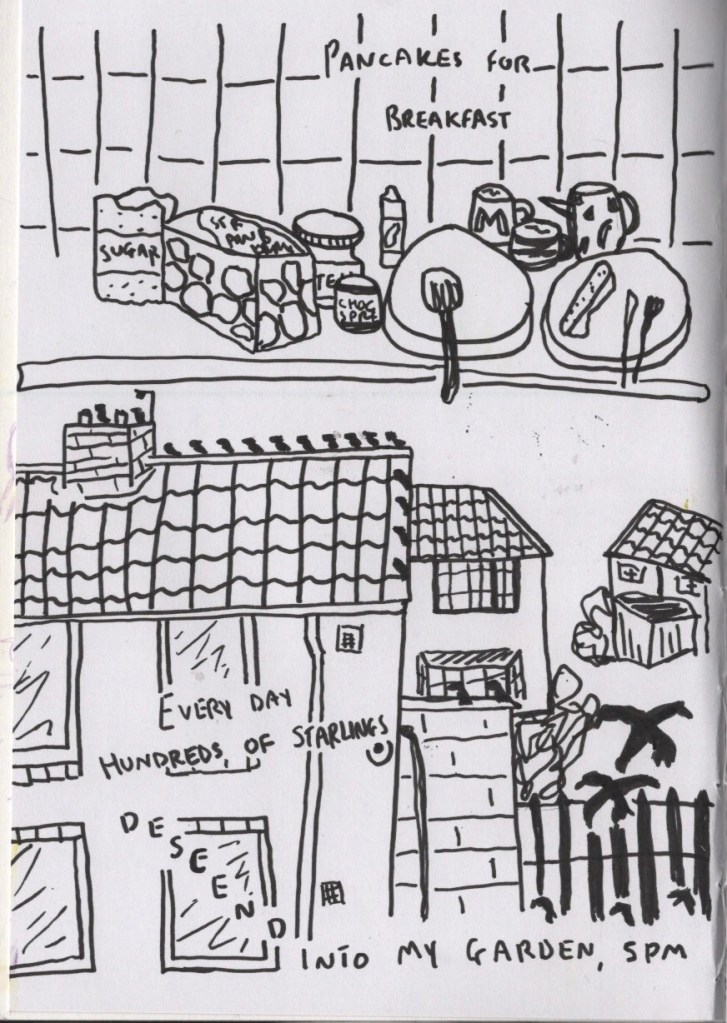

Using the archive of sketchbooks available on Hockney’s website, specifically focusing on the books titled ‘London 2002‘, ‘Norway 2002‘, and ‘Yorkshire 2004‘, I considered the potential relationship Hockney has with his sketchbooks and how I could translate his usage of them into my own style. It is clear that these sketchbooks go everywhere Hockney goes, living in his pocket or some other easily accessible location. This is made more apparent by the chosen names of each sketchbook being tied to the place and year they were completed in. Some of the content that Hockney chooses to draw is random and eclectic, which often happens when you are in mundane locations looking for something to draw. Every page features a landscape, object, or person, most likely drawn whilst waiting for something else to happen or just to record the moment.

All of the drawings and paintings throughout his sketchbooks have been done quickly, loosely, and using pens or watercolour without any preparatory sketches. He seems to favour only using one medium per sketchbook and a limited selection of it. London 2002, for example, features only black and red pen drawings. The pages are also often seemingly unfinished or quite empty. This is contrary to his usage of colour and the maximal usage of space in his paintings. Hockney’s signature usage of pattern remains, however, as he uses this to fill space or shade certain areas. It is inspiring to me to see how he uses line as texture in this way – something that I am interested in further developing myself.

It is clear that Hockney simply wants to get down what’s in front of him on paper. There isn’t a great deal of planning or consideration going into his sketchbook pages – he just starts drawing. His sketchbooks are the perfect example of taking the everyday and building off of it. You can see clearly how his sketchbooks have informed his creative process and how the messy and freehand drawings of random objects later become famous works of art.

The work in Hockney’s sketchbooks reminds me of Bryan Lewis Saunders ‘Under the Influence’ series. The drawings Saunders produced whilst experimenting with various drugs are very free, exploratory, and focused on getting information down on paper. They are intimate and personal works of art, and communicate Saunders unique perspective of the world as seen in that moment. Hockney’s sketchbooks do a similar thing – showing an insight into his perspective of the world. The viewer can’t always tell what’s in the image, and we don’t know the feelings Hockney was having or why he chose to draw what he did. In some regard, these sketchbooks will always remain personal and have things ‘hidden’ – experiences we can’t share with the artist.

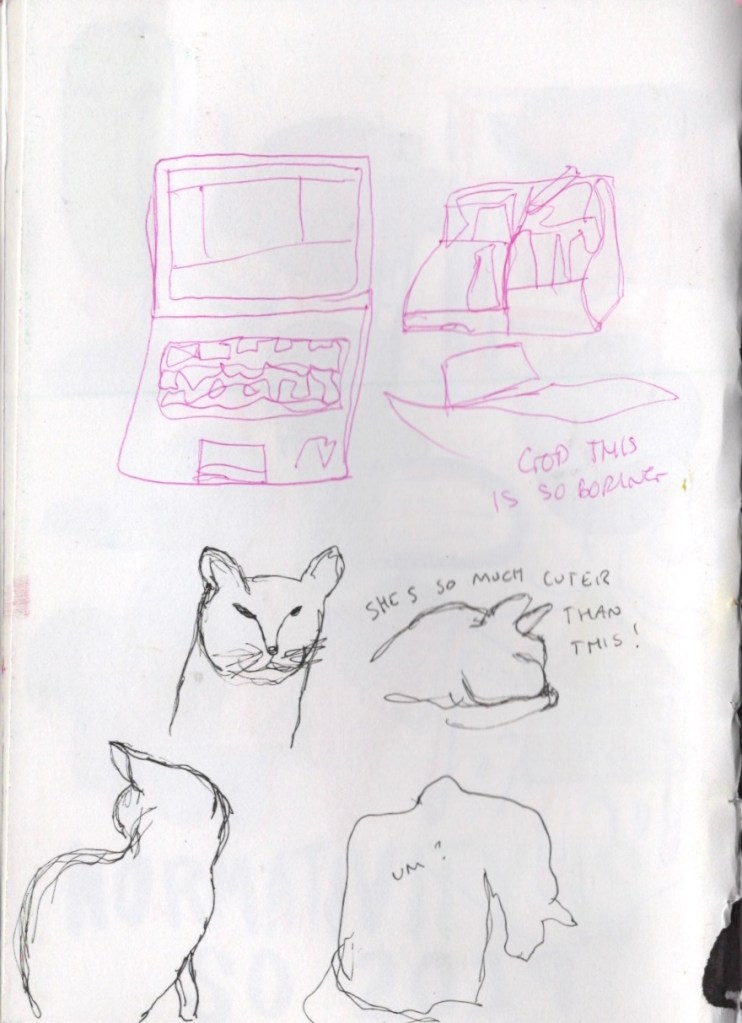

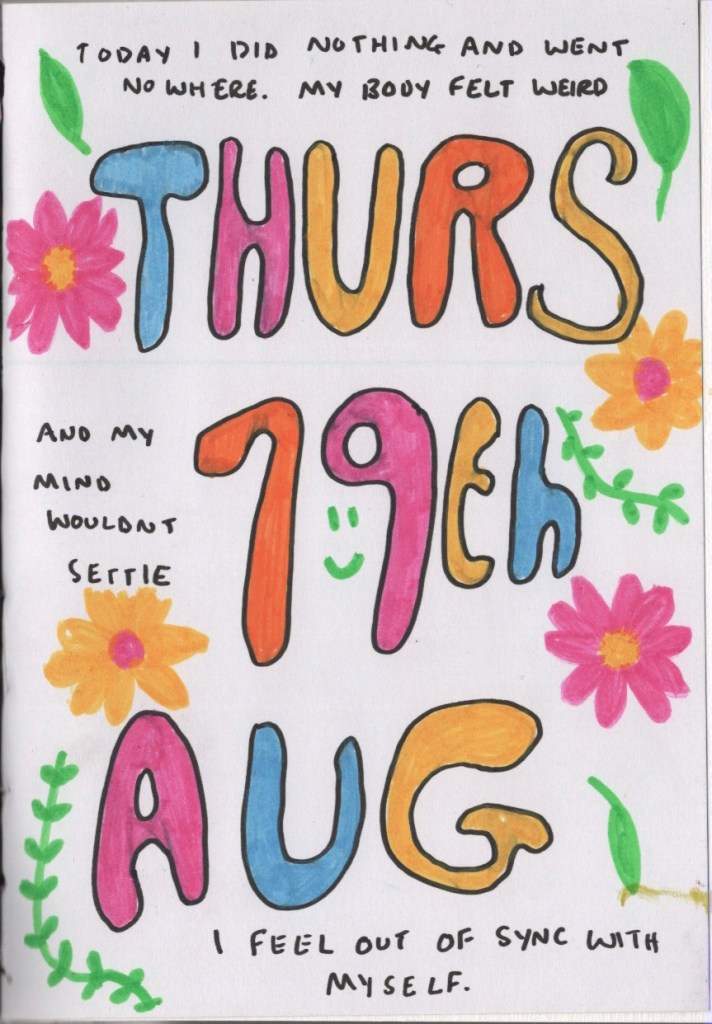

When I first looked at Hockney’s work, I felt overwhelmed by the idea of learning from it. Currently, my life is spent in the same few rooms of my house, as a combination of worsening health and the COVID-19 pandemic has meant accessing the outside world isn’t very easy for me. I felt I didn’t have moments to just draw random objects in, nor did I know how to go about drawing the objects I look at every day in a natural way. I wrote down that I needed to ‘be quick and eager in my sketching, worry less, capture moments, and draw what’s right in front of me’. I tried to do this – some quick sketches of the things on my desk and my cat but found it really boring. Then I sort of put it away for a while.

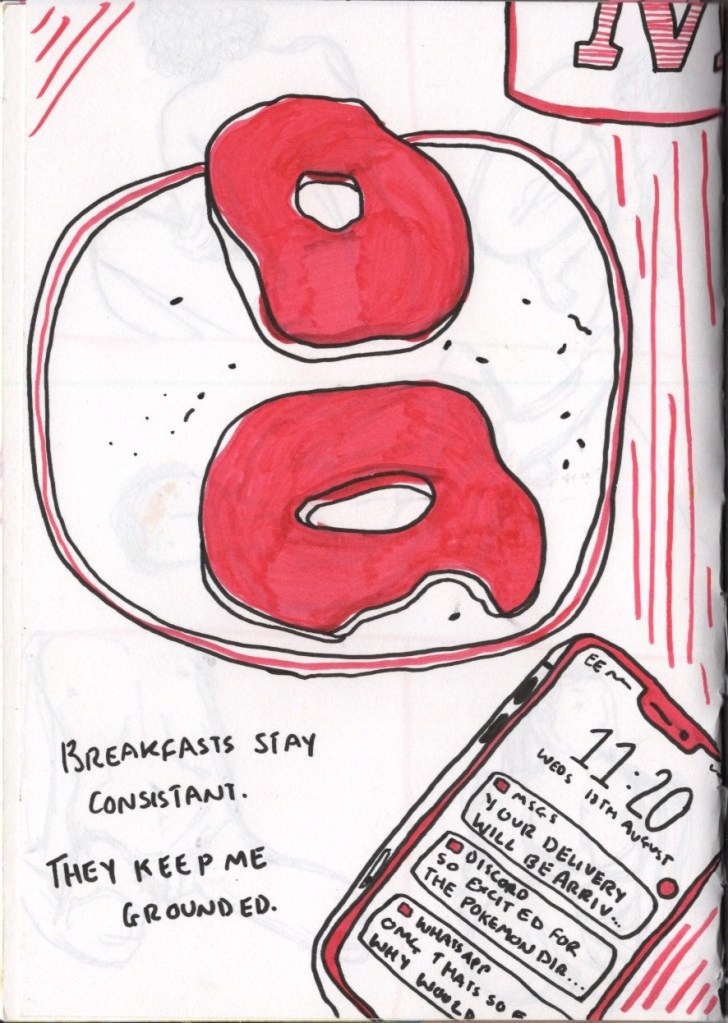

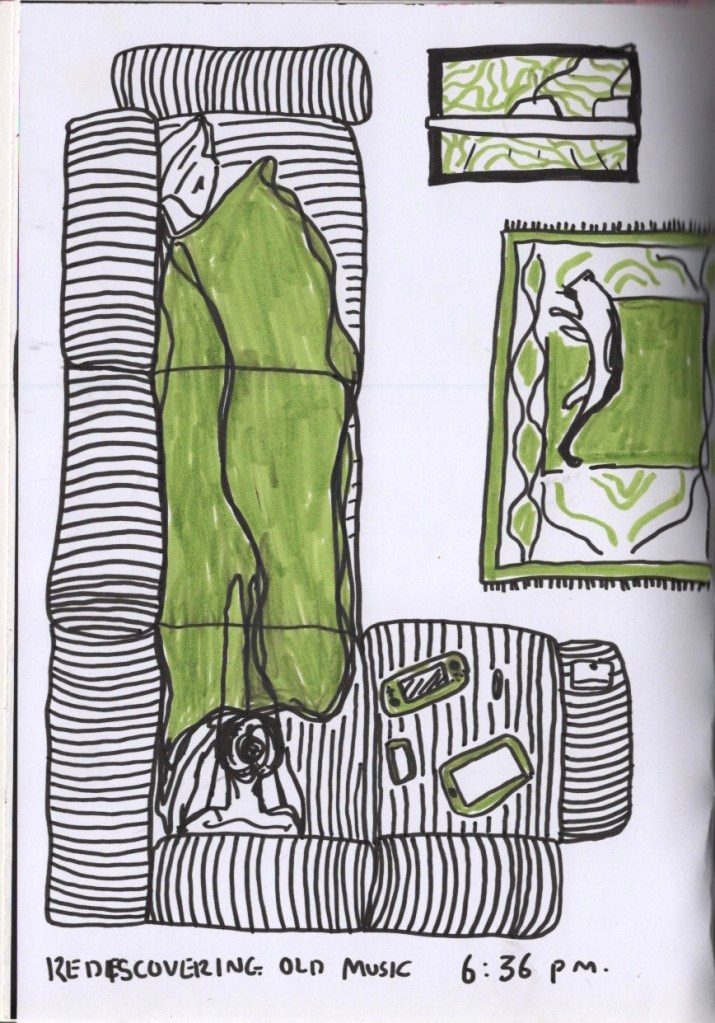

About a week later, I got an opportunity to go out to some local venues and tried hard to get some Hockney inspired sketching in. I only managed two pages, of which neither makes me happy. They did inspire future ideas and were definitely useful, but I didn’t find myself enjoying the process. I kept pushing myself to pick up my sketchbook and draw whilst in the little moments between things, and finally, I found my groove. The first page I did was page 24, and I was so happy with it. I felt I was working quick and effortlessly but was having fun and feeling inspired. I then proceeded to set a series of alarms throughout my day, at which point I had to draw whatever was happening – I only actually did it for two of them (pages 32 & 36), but I’m happy with the outcome.

Analysing Hockney’s work and considering his relationship to his sketchbook has hugely influenced how I have worked in my sketchbook throughout Assignment 1 – even if it isn’t immediately apparent. I spent a lot of time working quickly, focusing on getting information down on paper, and trying to see the world around me from different perspectives. I really hope that my relationship with my sketchbook grows to a point where I, too, have sketchbooks with similar names, documenting the different times in my life.

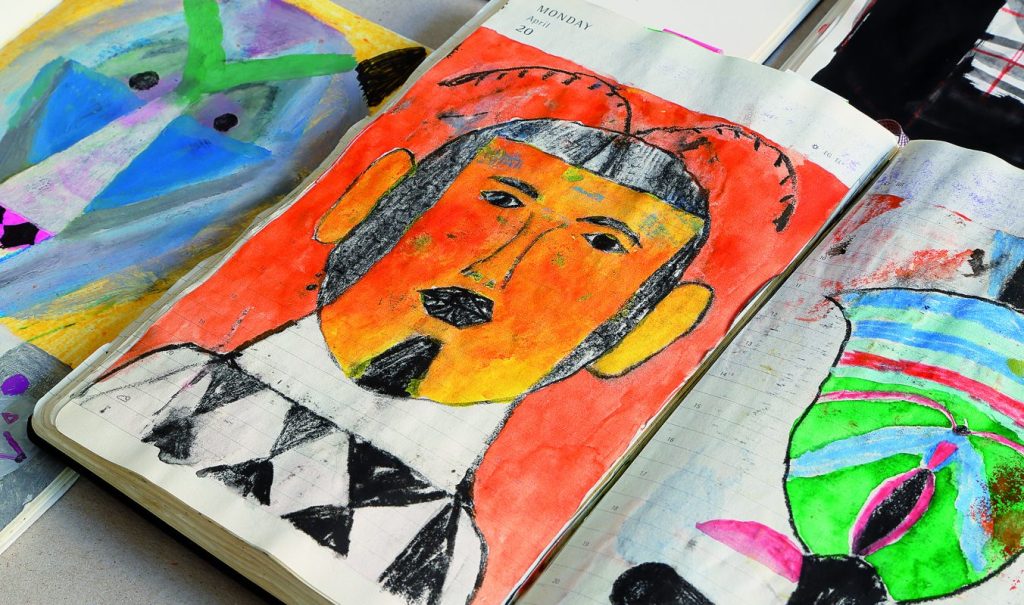

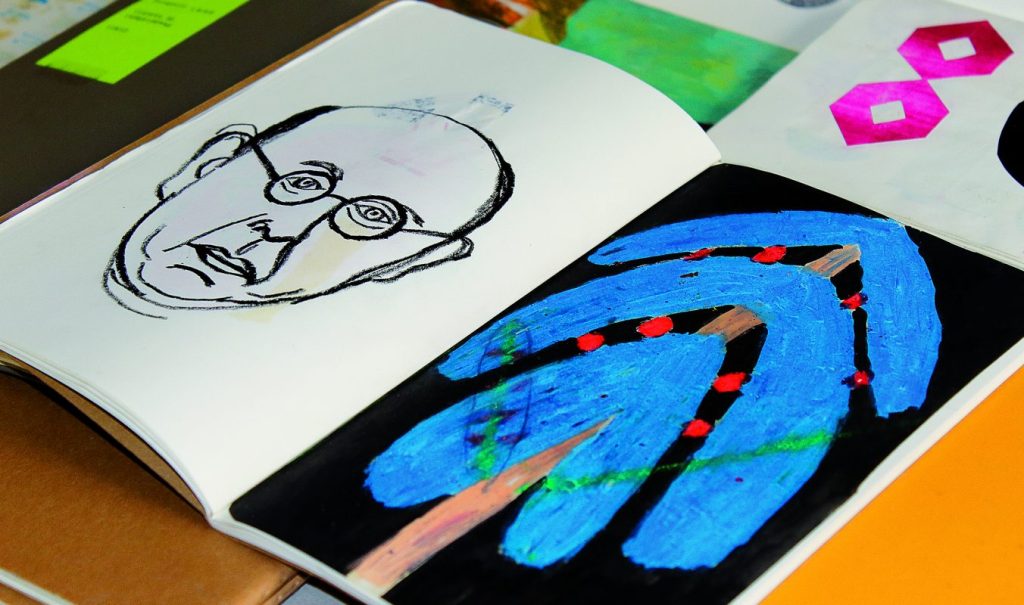

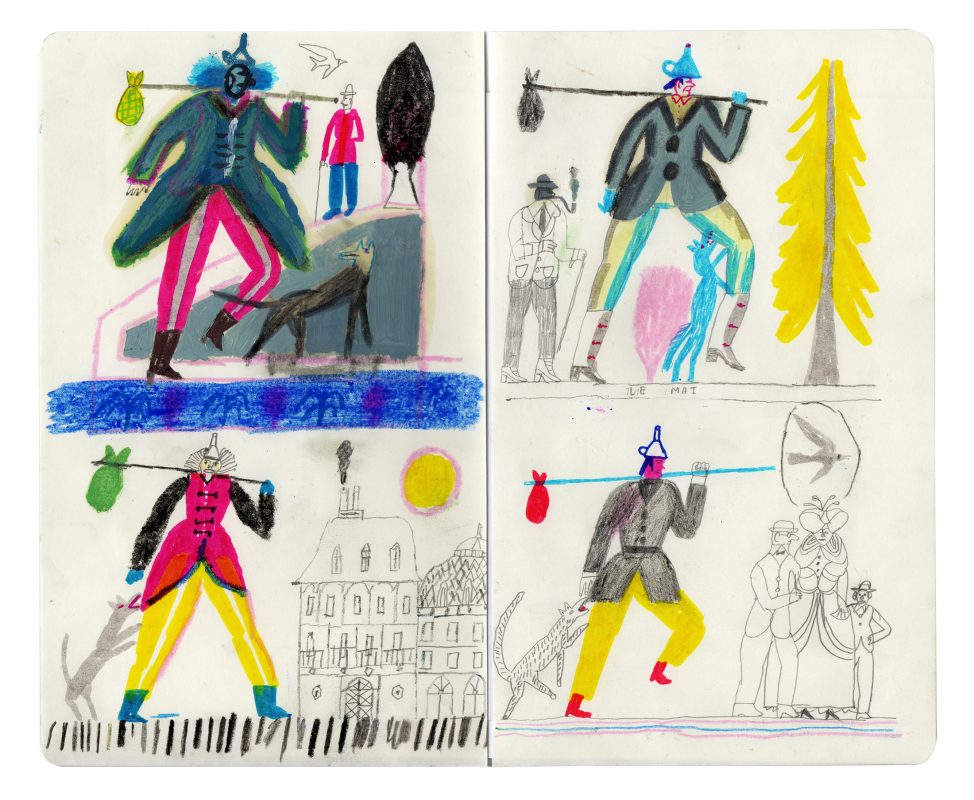

Jim Stoten

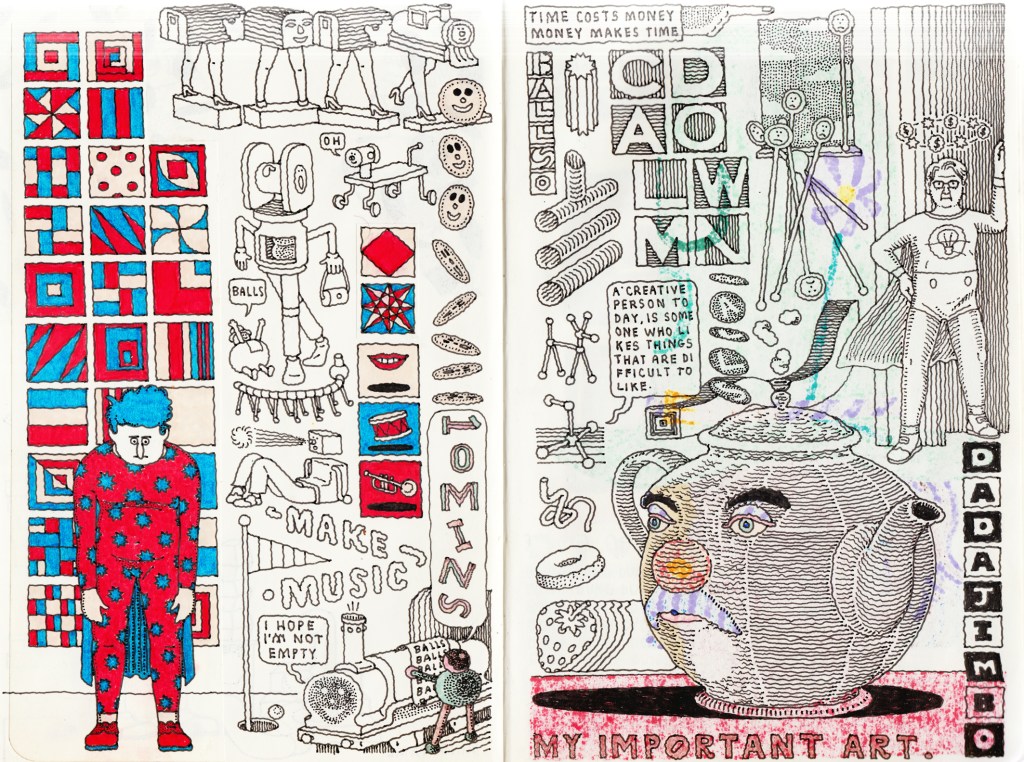

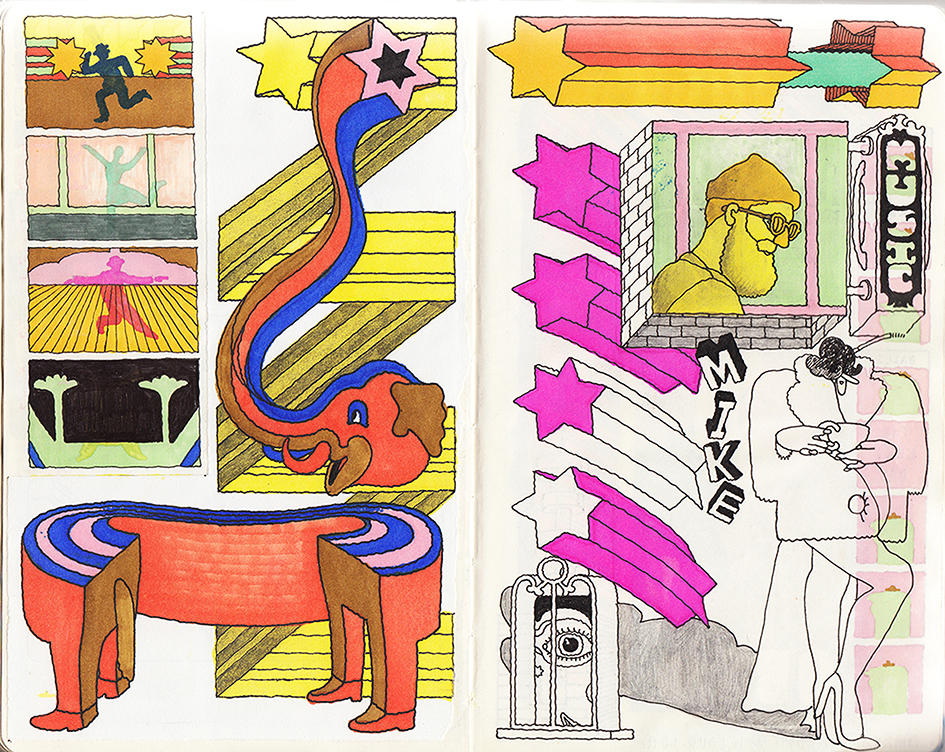

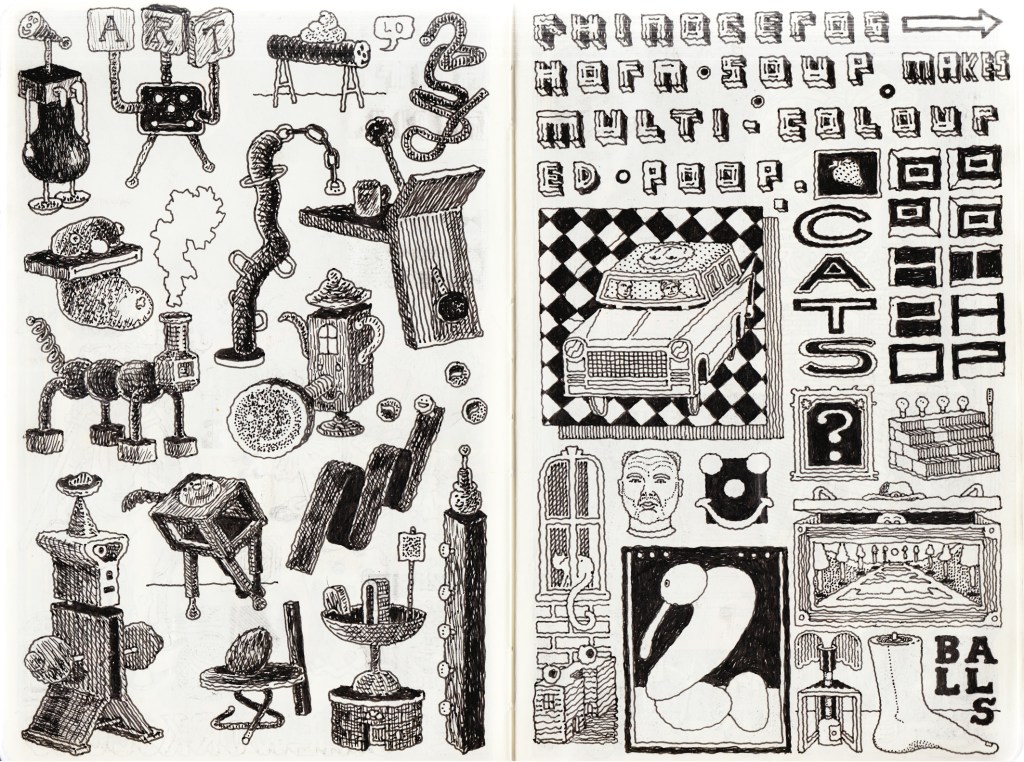

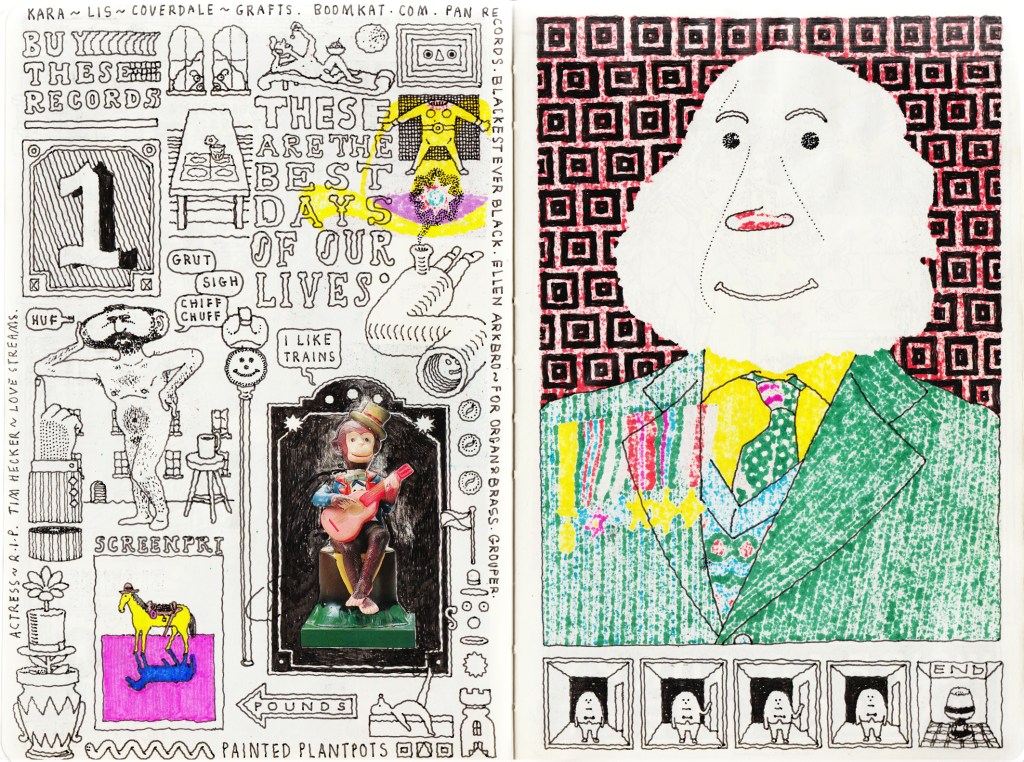

Skotchbook by Jim Stoten is a publication from Unseen Sketchbooks featuring a selection of work from Stoten’s personal sketchbooks. Stoten’s illustrations are wacky, nonsensical, and bursting with bright neon colours. He discusses on the Unseen Sketchbooks page for his book how using his sketchbook to record everything he thinks, hears, and sees helps him develop these pieces. The work shown in Skotchbook isn’t dissimilar to the illustrations Stoten creates for clients, but he explains that his sketchbook allows him to translate feelings and thoughts that don’t feel appropriate for commercial art.

I chose Jim Stoten to research for two reasons: first, I felt drawn to and excited by his artwork, and secondly, his approach to using sketchbooks was something I felt was deeply admirable. This quote from the Unseen Sketchbook page on his publication resonated especially with me:

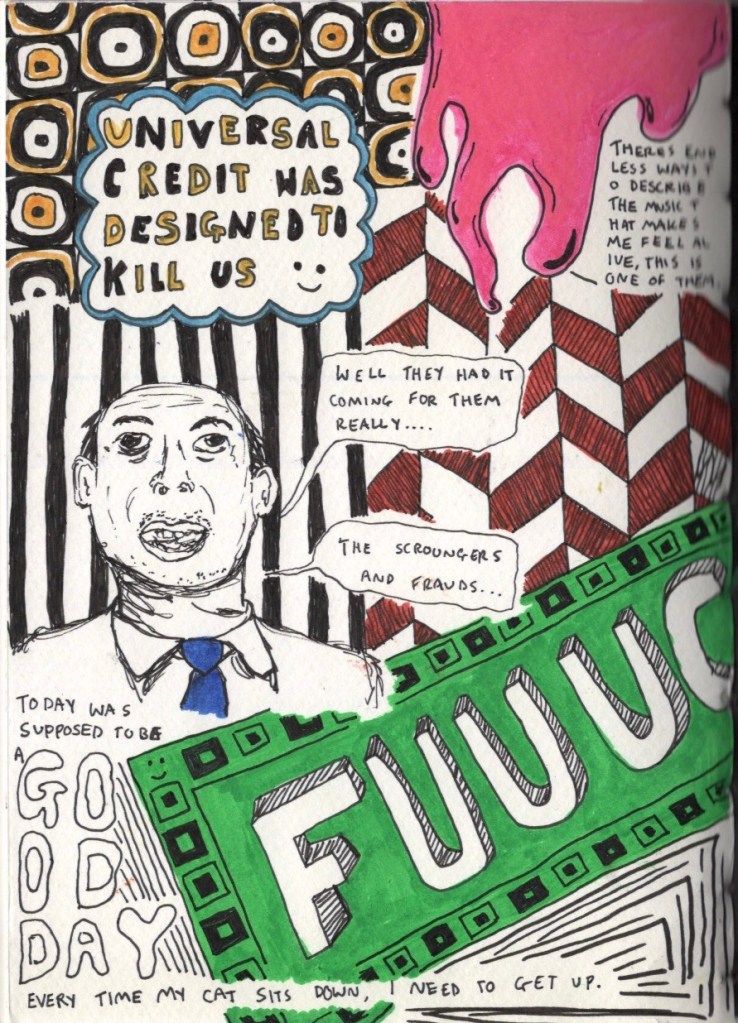

My sketchbook has a function much like a valve on a steam driven engine. Things go in there that do not, cannot and perhaps should not, go anywhere else. My work as a commercial and editorial illustrator does not always allow the creative freedom to transpose these thoughts and ideas into work pertaining to a brief of any kind, and so my sketchbook provides a balanced counter weight to the prescriptive and sometimes even instructional nature of commercial briefs.

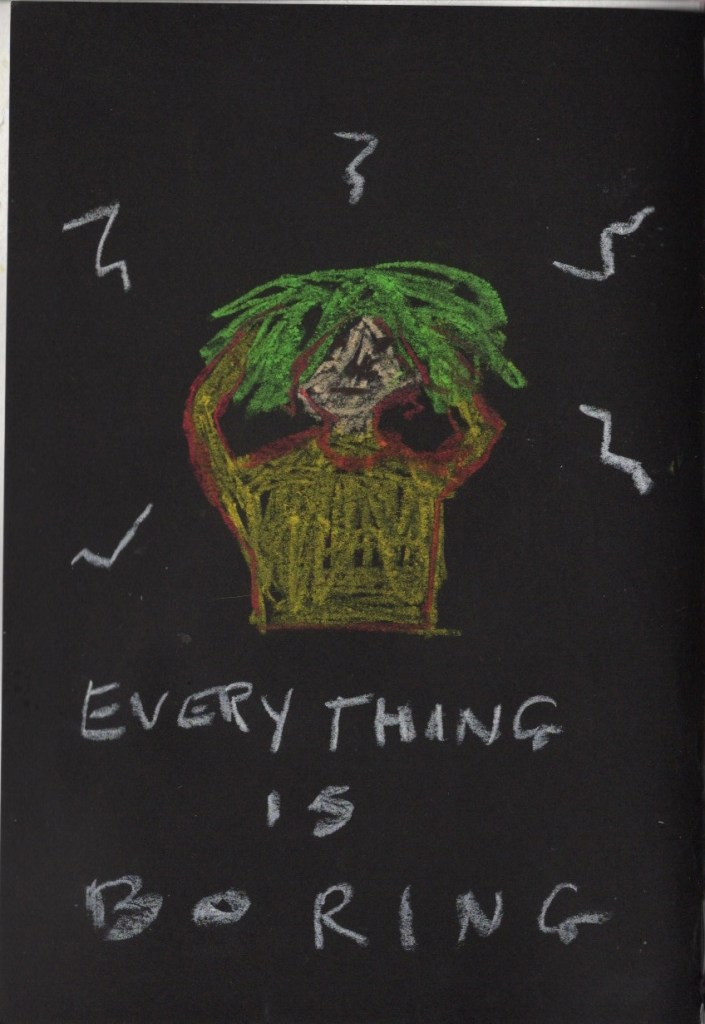

Throughout Key Steps in Illustration, I felt that whilst I enjoyed the process of designing for client briefs, I missed the ability to explore my own thoughts, feelings, and creative desires. I didn’t have as many opportunities to play around and make art that was meaningless and fun – something I sorely missed. The appeal of a sketchbook to me is the ability to have this place separate from any client work or official briefs, to record a part of myself, and let go. This is the bit that I am missing right now from my creative process that I am hoping to develop throughout this unit.

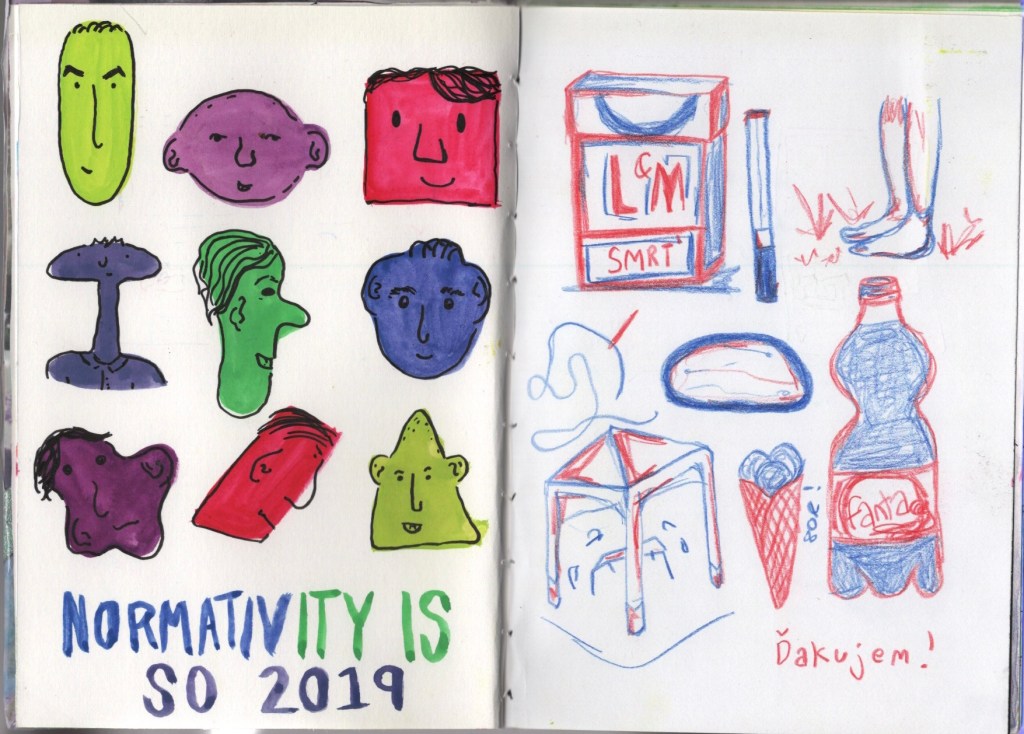

Jim Stoten presents the inner workings of his brain in a visually organised and clean way. Each page of his sketchbooks contains neatly collaged ideas, concepts, and thoughts, randomly placed with no real purpose. Stoten himself describes his sketchbooks as containing ‘comic strips that attempt to make sense of my own thoughts, feelings and reactions to the World…poems, hand drawn type, song lyrics, memorable quotes from films, TV, debate forums on all topics and interview chat shows from the 1970’s and 80’s….observational drawings from train journeys, exhibitions and visits to the pub, as well random drawings of imaginary people, architectural forms, modes of transportation and animals.‘ He truly includes anything and everything within the pages.

Some pages have the same bold, neon colours that Stoten uses in his formal illustrations, but they are usually used lightly or not at all. A black fineliner dominates the sketchbook pages, and Stoten makes use of white space and abundant patterns. Decorative typography is used to write passing thoughts alongside any drawings – though some pages are solely built out of type. I find it hard to find words to describe the work in his sketchbooks as I find myself mesmerised by it. I definitely want to work in a similar way.

Stoten and Hockney are approaching the same problem, and each has produced very different results. Both are trying to record and navigate their thoughts, the world around them, and the things they engage with. Where Hockney aims for speed, quantity over quality, and simply getting information on a page, Stoten has a more linear and methodological system to his pages. Neither is ‘correct’ – they are merely different approaches to observing your everyday experiences. However, there’s something about the approach that Stoten takes that feels ‘at home’ to me.

When I came to researching Stoten in full, I was already quite far into Assignment 1 and had spent a lot of time researching Hockney. I realised that a lot of the things I could learn from Stoten, I had already begun the process of learning from this research. However, the main thing that I feel I need to learn from Stoten is that it’s my sketchbook. I make the rules – it’s my place to exist freely and without limitation. Anything I want to put in it is allowed. Anything counts as art, and I can do as I wish. I need to be less afraid of things not being allowed in my sketchbook – when I’m the only one constricting myself!

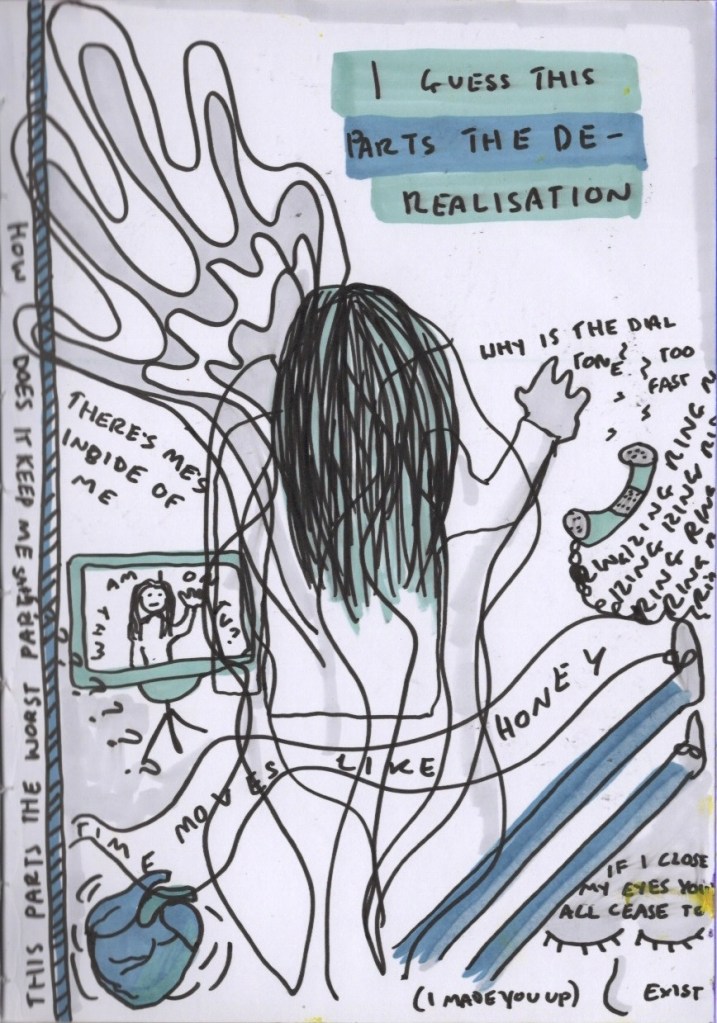

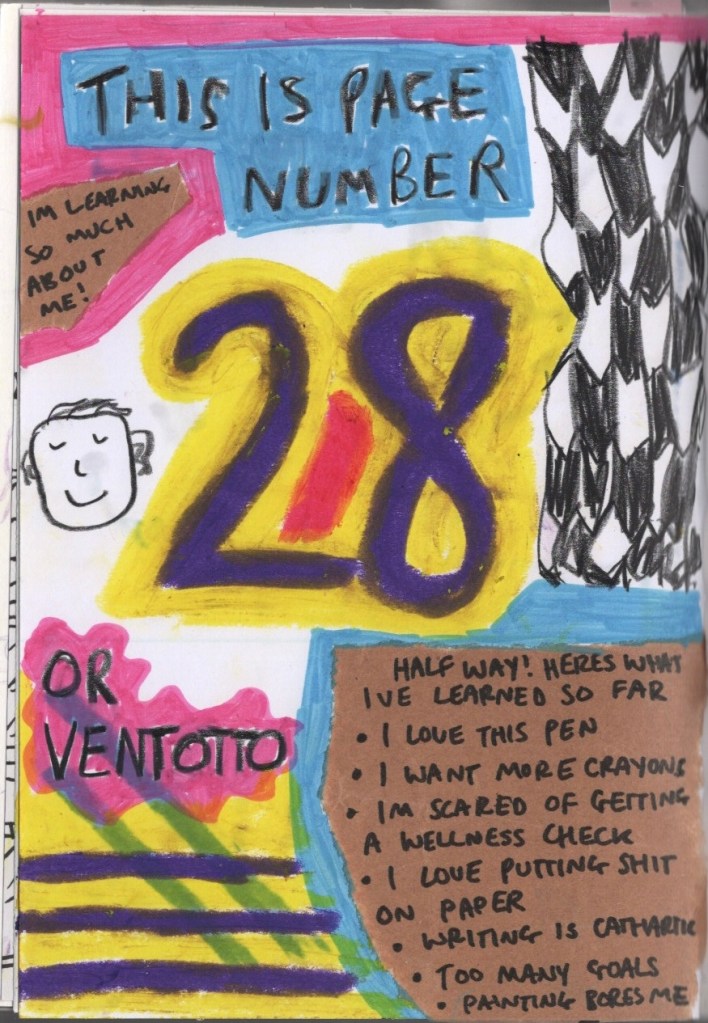

Other things to learn from Stoten include exploring my own thoughts and feelings, responding to music or other media I engage with, creating made-up things that I enjoy thinking about, and generally expressing myself a little freer. Where Hockney has inspired a sense of freedom in how I create, Stoten has inspired it in what I create. I feel like I have already started working towards these things whilst completing Assignment 1 in general, which you can read more about in my Assignment 1 learning log. Pages 13, 16, 27, 28, and 41, as well as some of my later work inspired by Hockney, all demonstrate this exploration. My focus on including more text in my sketchbook work has achieved this too.

A key difference in my work vs Stoten’s is that I have found I really enjoy using a 1.0 fine liner, which is considerably thicker and allows for less neat, orderly work. On a particularly stressful day, I decided to use an 0.5 fine liner and try out a page closer in style to Stoten’s work. I really enjoyed the process, and it felt cathartic to get my thoughts out in this way. I also love the final result – I feel it could be a piece of art in its own right. It did take a lot longer than my usual approach, but that felt okay as it felt like a process of letting go of built-up stress. I also felt like I was really breaking down barriers in my quest to allow myself to put whatever I want in my own sketchbook. I think I will opt to include an 0.5 pen in my pencil case now, just in case I want to do something like this again.

Whilst researching Jim Stoten, I used his website alongside the Unseen Sketchbooks page for his book. He has excerpts from his sketchbooks on his website, which can be found here. Examples of his other work can be seen here.