This research task asked me to look again at reportage illustration and explore different approaches and uses of the artform. First, I was provided with a list of contemporary and historical artists who focus on reportage illustration. I had a brief look through each artist’s work and made notes on what inspired me, how I felt, and what I thought. This led to some interesting topics to consider and reflect on and ultimately helped me solidify my relationship with reportage. Next, I was asked to read a series of articles and reflect on a specific usage of reportage illustration.

The artists provided in the exercise brief demonstrated a wide range of approaches to reportage illustration and being able to explore this further was very insightful. I noted that I was particularly drawn to playful and expressive styles, such as the work of Laura Carlin and Louis Netter, rather than more accurate and detailed work. I also got to look at some sketchbook work specifically (Lucinda Rogers and David Gentleman), which I am learning to cherish throughout this unit. Seeing how other artists use this space is inspiring and comforting. Of all the content chosen within these pieces of work – the drawings of buildings are the ones that inspire me the most. I love drawing architecture and examining buildings up close. The intricacies of the man-made world are fascinating to me.

By the fifth artist, I was beginning to realise that this just isn’t for me. I can appreciate the skill and method artistically, but I have very little interest in doing it myself. Sure, sketching what you see day to day is useful, but I have no desire to focus on it or develop it further. I noted that despite the variation in mediums, content, and approaches, all reportage illustration artists seem to have a deep passion for capturing the world around them. They all discussed the importance of everyday moments, recording them, and how they enjoy doing this. It’s helpful to know that I don’t want to pursue this avenue. It crosses one thing off the list and allows me to focus on the areas I am interested in.

When I reached the work of George Butler, I had to pause to think about the wider conversation around his artwork. I felt it didn’t accurately represent the environments he was drawing in – something I feel is vital if you’re going to try to capture the realities of war. Photography, in my opinion, is a better medium in this circumstance as it lends itself more to expressing the feelings and experiences of the subject matter rather than of the artist. Centring those who are living through war should be the priority. Veronica Lawlor’s work is a good example of this. It contrasts with Butler’s as she was living in New York as a regular citizen when the 9/11 terror attack occurred. Her documentation of this event was a continuation of her documentation of the everyday. It just so happened that a terror attack was her everyday.

Butler, on the other hand, specifically chooses to go into wartorn areas for the sake of sketching them. This feels intrusive and contributes to the concept of ‘white saviourism’. There’s nothing progressive or valuable about a wealthy western white man travelling to impoverished and war-stricken middle eastern countries only to then win awards by showing off his experience of ‘war’. He hasn’t experienced war. His art will always be an outsiders perspective of the events he documents. The glorification of his work is decentring the lived experiences of those in the war. We should be focusing on artists who are creating work whilst living in a city that they know as their home, experiencing air raids and military pressure. These artists do exist, but instead, we focus on people like Butler and reinforce this idea that those in the middle east (and other non-western countries) are helpless and weak.

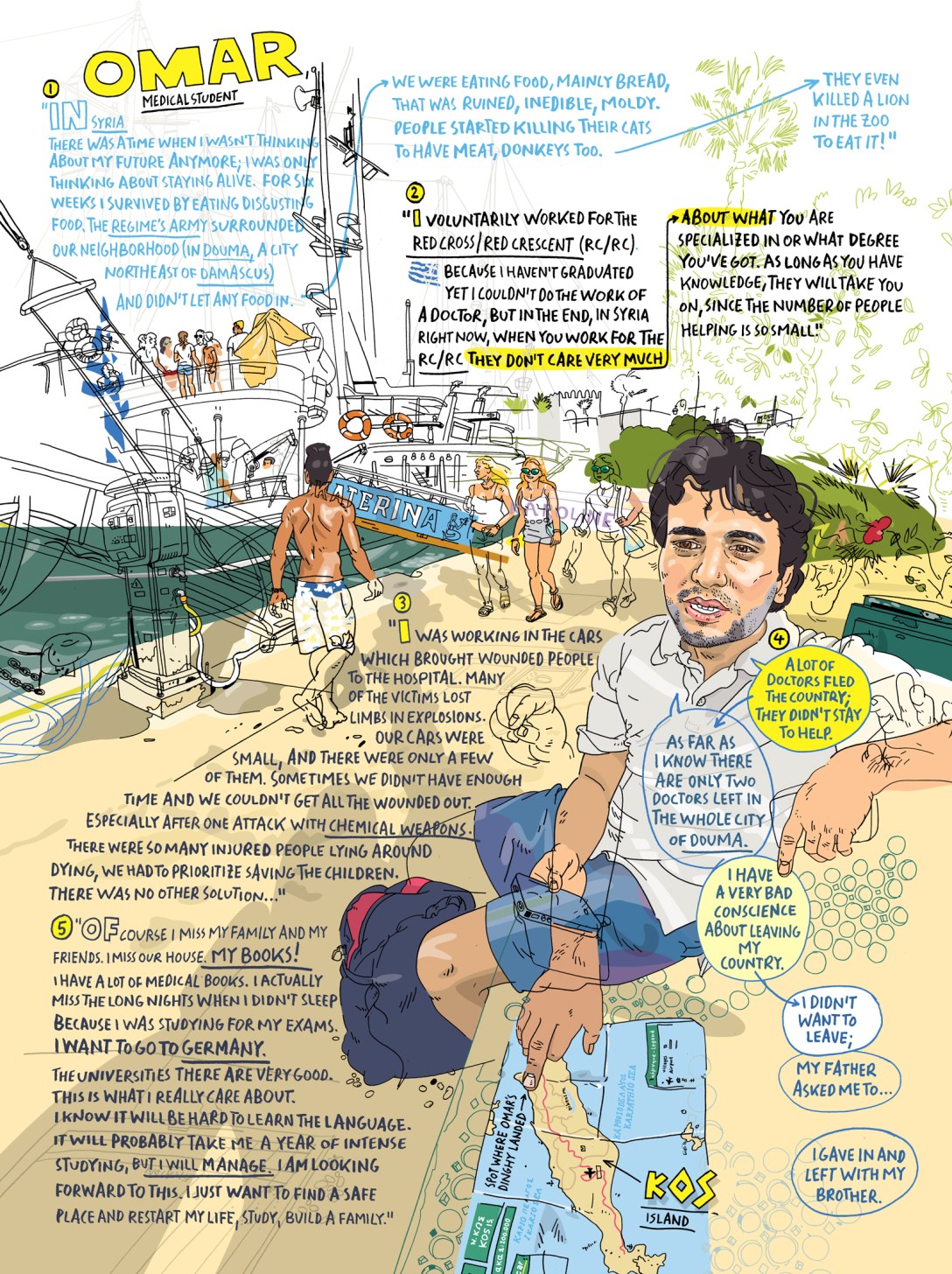

Ultimately the power an artist has is the ability to choose what content to include and to remove from their imagery. An observer of a situation such as war cannot accurately make these decisions in a way that represents the lived experiences of those within the situation. The artist’s opinions, feelings, and biases towards the situation will ultimately prevail. An example of being an observer whilst centring those in the situation is the work of Olivier Kugler, who presents illustrations alongside text in an incredibly matter of fact way. It is clear he tries to represent those in his illustrations accurately. His work almost presents as infographics, describing to the viewer what is happening in these situations and how people feel about it. It is honest and raw and not intended for Kugler’s own gain.

The question I was left with after considering this topic was, ‘Is going into someone else’s everyday for the sake of your creative advancement intrusive?’. I continued looking through the rest of the artists, then, to my surprise, realised that the articles provided in the second part of the brief were about this exact topic. The exercise states that ‘drawing within a war is far removed from the everyday’, and I would have to disagree with this. For many people across the world, this is their everyday. What ‘everyday’ looks like is subjective and unique to everybody. Many of us in the west have enormous privileges, but that doesn’t mean everyone has those privileges. To disregard this reality is the very meaning of privilege.

Upon reading the articles, I was amused to see that Olivier Kugler was one of the focuses [1]. The article’s writer perceived his work similarly to how I did – stating, ‘His illustrative style is subservient to rigorous research and inquiry’. Exploring Kugler’s work in-depth further showed how he actively aims to represent his subject matter in the most accurate ways. His work is not about him – it is about giving a voice to those who most need it, rather than inserting his own. Stacey Clarkson James is quoted in the article as saying, ‘He foregrounds the voices of the refugees’, which eloquently describes Kugler’s processes. In trying to capture the everyday of those in situations we may never be able to imagine, Kugler is a perfect example of an artist using their privilege to centre those who are not afforded the same.

The other two articles focused on the works of Edward Ardizzone [2] and the book The Photographer by Didier Lefèvre, Emmanuel Guibert, and Frédéric Lemercier [3]. Both were insightful reads and provided different contexts to war reportage. Ardizzone documented the Second World War – a moment in time when photography wasn’t widespread nor easy to accomplish in such environments. Of course, in a situation like this, documenting via sketches and drawings is the only way to capture the events happening in the world. He wasn’t gawking or using the experience to further his career – he was performing a necessary service. Recording events such as war isn’t inherently wrong; it just requires a level of nuance. In the modern-day, the appropriateness and focus of your artwork should be considered in relation to the world around you. The ‘why?’ is as important as the ‘what?’.

The Photographer, on the other hand, feels a little out of place in this discussion. The book explores the experiences of Lefèvre, a photojournalist who travelled to many countries in active war. It tells a story of his trip from Pakistan to Afghanistan and features his photographs alongside illustrations and text in a graphic novel format. Rather than a display of Lefèvre’s reportage, it is a detailed account of his experiences. While this also does not centre the voices of those living every day in war, at least it is transparent in doing so. The book, if anything, is about photojournalism and the trials and tribulations it can include – it just so happens to take place within a war. It’s not speculation of how the war might feel to those living in it or how it felt to witness it for a handful of days. It’s plain and clear: Lefevre had this experience, and here is his account. Whilst still showing insight into the realities of war and referencing reportage, this is very different from the work of Kugler, Ardizzone, and Butler. Photojournalism seeks to be informative first and foremost, and as I initially mentioned, it seems the more appropriate medium for war documentation.

Interestingly, this article was the only one to acknowledge what I am discussing here, referring to it as ‘intrusive and voyeuristic’. The fact this was specifically referencing photojournalism, alongside the lack of acknowledgement in the other two articles and the overall narrative of Part 3 thus far, makes me curious about why photography is still considered to be the lesser of the two mediums. Reportage illustration can be just as harmful and, if anything, considerably more dangerous in its subjective nature. However, the act of ‘doing it yourself’ places it in much higher regard. Photography is viewed as easy – anyone has the capacity to take a picture. But being there, in a war, and drawing something??? That is deserving of praise!

Disregarding the fact that photography is a skill and does, in fact, require more than just pressing a button – this view contributes to the centring of the privileged artist rather than the unheard voices of the war. Looking at the illustrations in awe at the remarkable ability of the artist to go to such a place and draw in such conditions causes the point to be missed quite spectacularly.

Ultimately the cultural context of the work we are creating as illustrators and designers needs to be carefully considered in our practices. If reportage illustration is what speaks to you, and you specifically want to report on situations such as war, you must be sure to be nuanced in your approach. Even in other areas of illustration – depicting an experience that is not your own requires such thought. We must also continue to remember that our western experience of ‘the everyday’ is one of great privilege.

References

Articles quoted sourced from the unit materials: https://www.eyemagazine.com/feature/article/olivier-kugler-bearing-witness [1], https://eyemagazine.com/feature/article/ardizzone-at-peace-and-in-conflict [2], https://eyemagazine.com/opinion/article/framing-the-evidence-of-war [3]

Image by Olivier Kugler, sourced: http://www.olivierkugler.com/