To start Part Four, I was asked to take a look at the history of typography along with writing, reading, and printing, and learn how they are intertwined. I was prompted to choose an area specifically to research – something that interests me or is relevant to my work – and to collect examples of ways type has been used in that area.

I found the introduction to the history of typography written in the unit to be very Eurocentric, despite mentioning that Europe and the West generally were not the first to develop new methods of producing type. I was quite disappointed to see this focus as typically, the OCA has been good at rejecting Eurocentric biases. I identified that this is an area I wanted to research for myself, to ensure I’m not ignoring that we are not responsible for modern typography.

Whilst Wikipedia is not necessarily the greatest resource for research, I find it a good starting place for large topics that you know very little about. I began reading through the page for Printing and was shocked by how differently the OCA PDF had portrayed the history of type. The PDF mentioned that woodblock printmaking goes back as far as 220 AD in China, but then skipped over hundreds of years to discuss Europe.

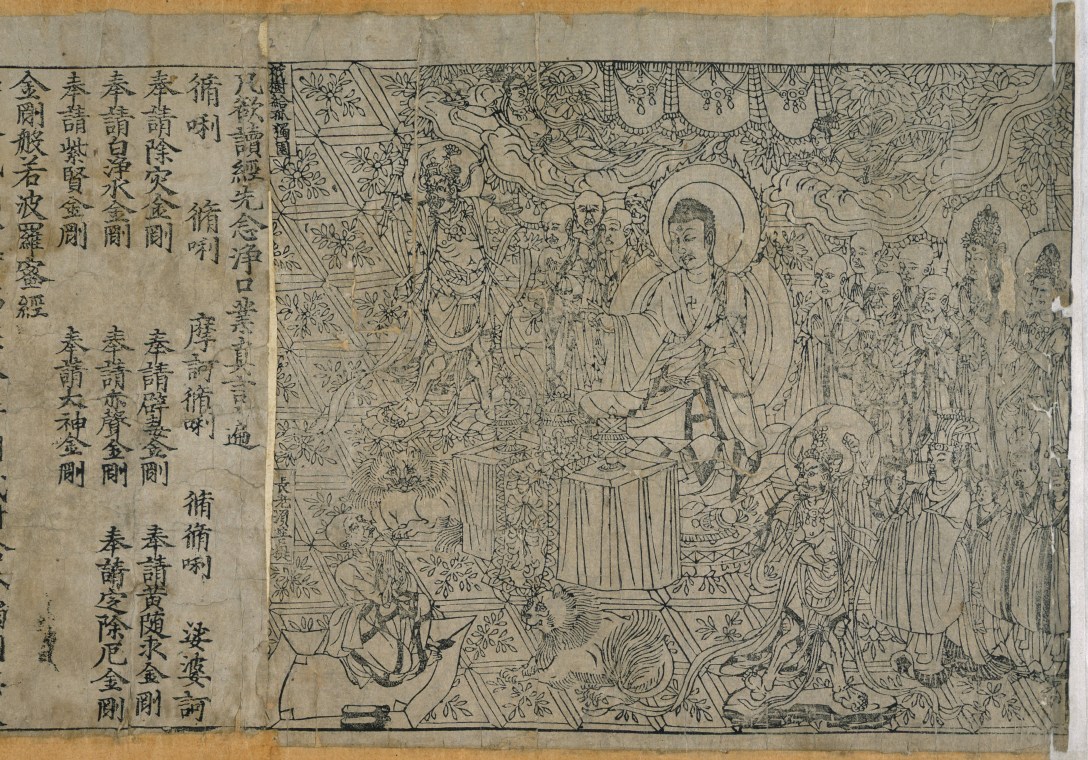

I learned that in the 7th Century, the Chinese woodblock printers started printing on paper, as well as fabric. The first printed book that we are aware of is from 868 AD, and by the 10th Century mass-produced books were widespread across Asia. Woodblock printing on paper was not common in Europe until the 1400s, 800 years after the first known paper prints were made in China. However, Europe is usually credited with the invention of movable type printing systems, specifically Johannes Gutenberg is known to be the person who ‘revolutionised’ print.

China created the first movable type system in 1040 using porcelain. It wasn’t as popular in China due to the sheer number of characters used in Chinese writing. Gutenberg was still not the first to use metal movable type, this being invented in Korea around 1230. Gutenberg’s ‘invention’ was brought to Europe almost 400 years after its initial invention in China. Historians now have confirmed he used the Chinese-Korean technique of printing, the only difference being its popularity with Latin alphabets.

Gutenberg may have enhanced printmaking by experimenting with varying inks, metals, and mechanical efficiency, but he certainly did not invent movable type. Europe was considerably immature in its development of print, and almost all of the systems we use originated in Asia. As usual, we took from them and acted like it was our own ideas, and the almost century-long gap in usage shocked me. How we don’t learn about this as a default is really surprising to me.

I felt quite frustrated that I had to go and look this up for myself to know about it, as I felt like it should be basic knowledge included in a design degree. I have increasingly wondered why all design history is Eurocentric in nature – Germany, the UK, Switzerland, and Russia dominating the industry – and would like to expand my understanding better. I spoke with some fellow students about this issue and got some fantastic book recommendations, some of which I have bought already and some of which I’ve added to a wishlist.

One book I purchased was Graphic Design: A History by Stephen Eskilson which unfortunately immediately skips over the history I described above, and begins with Gutenberg in Europe. I hope to read this further, however, and hopefully learn some more global design history. I’m looking forward to exploring more of the books recommended and challenging the narrative that Europe is responsible for modern-day design.